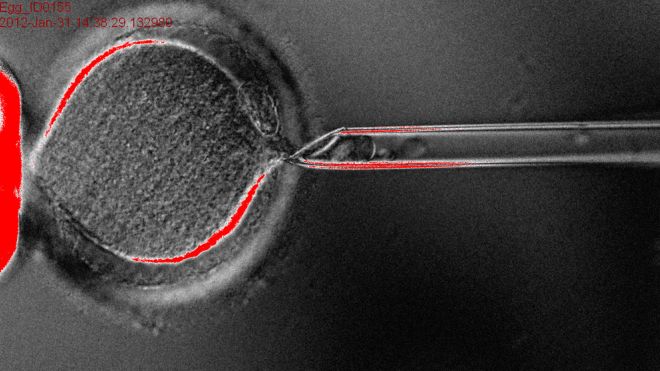

A headline-making paper last week announcing that scientists had, for the first time, cloned human embryos and harvested stem cells from them contains minor errors, the authors acknowledged on Thursday.  The mistakes raised questions about how well the journal that published the paper vetted it but probably do not undermine the study's central claim. In a statement, the journal, Cell, said “there were some minor errors” in the paper, but “we do not believe these errors impact the scientific findings of the paper.” An anonymous commenter on the website PubPeer, where scientists discuss papers after they have been published, first pointed out problems with the paper, which drew extensive media coverage. Even before the errors were spotted, however, there was concern among experts not involved in the study that Cell had rushed publication. It received the manuscript on April 30, tapped outside scientists to review it in the standard process called peer review, asked the authors to make revisions based on that review and accepted the paper on May 3. When asked about the short turnaround time last week, Cell spokeswoman Mary Beth O'Leary said the paper “underwent a rigorous peer review and editorial process.” Outside experts disagree. A three-day review process “is almost impossibly fast,” said cell biologist Jim Woodgett of Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, Canada. “To have a paper like this received, reviewed, revised and accepted so quickly is very, very unusual.” In a statement on Thursday, Cell referred to “the preeminence of the reviewers” (whom it would not identify) and said it has “no reason to doubt the thoroughness or rigor of the review process.” The rapid turnaround was possible because the reviewers “graciously agreed to prioritize” the paper. DOLLY REDUX The paper described how scientists led by biologist Shoukhrat Mitalipov of Oregon Health & Science University accomplished what others had failed to: “therapeutic cloning” in humans. That procedure begins with a human egg. The Oregon scientists removed its genetic material, or DNA, then took an adult skin cell and fused it with the egg. The DNA in the skin cell took over, causing the egg to begin developing as if it had been fertilized. This “somatic cell nuclear transfer” was used to clone Dolly the sheep in 1996. But in this case, the goal was not a human being; Mitalipov said last week that scientists would not implant the dividing embryo into a womb so that it could develop into a baby. Instead, the aim was a dishful of stem cells, which can morph into any of the 200-plus cells in the human body and might be used therapeutically, such as to replace cells lost to degenerative diseases such as Parkinson's. After a few days, the human embryo contained exactly that: stem cells that the Oregon scientists could use to start cell lines. The errors in the Cell paper involve photographs and data plots, something OHSU spokesman Jim Newman said was “an editing error, not issues with the research or the data itself. “OHSU agrees that there were some minor errors made when preparing the figures for initial submission,” Newman said, adding that the university does not believe the errors “impact the scientific findings of the paper in any way. We also do not believe there was any wrongdoing.” In one case, an image described as a cloned stem-cell colony is reproduced in another image, where it is labeled an embryonic stem-cell line derived from in vitro fertilization (IVF), not cloning. Mitalipov told the journal Nature that the label is wrong, and that another labeling mistake explained other duplicated images. Another error was in images purporting to show that the genes that are turned on in stem cells derived from the cloned embryo (such as genes that make a cell a neuron) are similar to those in stem cells taken from IVF embryos, considered the gold standard for embryonic stem cells. The point was that the stem cells taken from the cloned embryos are true stem cells. The problem, said the anonymous reviewer on PubPeer, is that the two images - genes activated in IVF stem cells and in clone stem cells - are suspiciously identical. Mitalipov said one image used the wrong data, and that he and his team are correcting it. While the mistakes seem innocent, they raised concerns among stem-cell researchers because the field has been struck by fraud in the past. In 2004 scientists led by Woo Suk Hwang of Seoul National University claimed to have produced human embryonic stem cells through the same technique used by the Oregon team. Their paper, published in Science, turned out to contain fabricated data. That came to light when scientists figured out that some of the images in the paper were copied or manipulated. “When I read the Hwang paper, I didn't find any glaring problems” at first, stem-cell biologist George Daley of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute said, explaining how difficult it is to spot fraud. “I am waiting to learn more, but there is a difference between errors in photomicrographs and fraudulent production of cell lines,” he said. So far, most scientists' ire is being directed at Cell more than the Oregon researchers. “To thoroughly evaluate the claims requires delving into the data, and you can't expect people to do that in a day or two,” said Mount Sinai's Woodgett, referring to peer review. “You're forcing them to be superficial.” Science journals compete intensely for “hot” papers, which can translate into headlines, subscriptions and advertising. Cell is published by Elsevier, a division of Reed Elsevier . Six years ago, Nature held up by six months a paper by Mitalipov in which his team used the Dolly method to clone monkey embryos, the journal reported on Wednesday. Scientists sometimes shop around hot papers, seeking a journal that will publish it fastest. Mitalipov told Nature he was in a hurry to get his Cell paper out before a stem cell meeting in June.source : http://www.foxnews.com/health/2013/05/24/errors-in-cloning-study-cast-doubt-on-publication-process/